Protecting public interest journalism ruled to be a key plank of democracy

I finally managed to read through the 160-page Cairncross Review: A sustainable future for journalism, a full year on since the final report was published and five months before the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) publishes its ‘final report’ concluding its own two year investigation into the practises of online platforms and digital advertising. The CMA report will explore possible measures to promote greater digital advertising pricing transparency, attempting to counteract the distorting effects of near total dominance of digital advertising market share by Facebook and Google.

Because of the length and complexity of the Cairncross Review, I thought it worthy of two Agility PR blog posts: Part 2 will follow by the middle of March.

The Cairncross Review focuses hard on building a well-evidenced picture of the decline of national and local media journalism in the UK (with parallels noted globally). The period for which many of the statistics cover is 2007 to 2017, a decade in which the press saw massive change as the nature of advertising and readers’ consumption of news went through what could best be described as a ‘digital switchover’.

Circulation and readership numbers fell like a stone

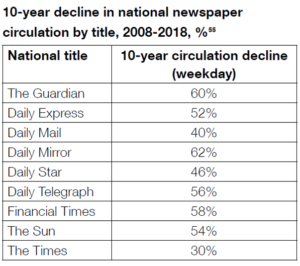

This was an extraordinary period of contraction of both national and regional publishers’ traditional sources of revenue: display and classified advertising and paid for ‘hard copy’ subscriptions. During this period, sales of both national and local printed newspapers halved and kept on falling, albeit at a slightly slower pace today. Print advertising revenue declined further still – by a whopping 69%! The statistics on falling circulations across key nationals are below:

Print circulation across those nationals halved from 11.5m to 5.8m between 2008 and 2018. And local print circulations also halved from 63.4m in 2007 to 31.4m. During the same period the number of local newspapers decreased from 1,303 titles to 982.

What happened to precipitate this rapid decline in print readership? Many of us have simply stopped buying and reading hard copy local, regional and national newspapers. So, today 74% of UK adults use some online method to find news each week and 91% of 16-24 year olds have already gone digital-only in their news consumption, relying increasingly on online platform news aggregators like Google News, Apple News or Facebook to serve the sort of news they expressed a browsing history-based preference for. The numbers don’t lie: in just five years from 2013 to 2018 the number of UK adults reading a hard copy newspaper each week dropped from 59% to 36% and only one in 10 people read a local newspaper weekly today.

Democratic deficit

So, what you might say? It’s inevitable that digitalisation rips through every market – why should the media be any different? It matters because ultimately democracy is at stake! The democratic deficit that flows from the reduced scrutiny of our masters; locally, regionally and in Parliament is the area which the Cairncross Review explores in some detail – identifying the effects of the decline of Public Interest News journalism as follows:

- Threatens community cohesion

- Undermines public accountability

- Jeopardises democratic legitimacy

- Forcing declines on local election turnout

- Local finances not as well managed (because they are exposed to less scrutiny)

- Discussion of local council activity falls

- Investigation of abuses of power falls

- Proceedings of local Magistrates Courts drops away

If you want to look at the detail behind this democratic deficit you can look at one report conducted during 2012-2016 which found that during this period court reporting fell by 30% in nationals and 40% in the regionals.

Another area which is witnessing a decline in resourcing is investigative journalism which essentially demands an exponential amount of high quality journalist time, sometimes with no end result in terms of column inches and circulation spikes. But we all know the value of this type of journalism when we see it.

Take the Guardian and Observer’s campaign to uncover the truth about Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook-harvested user data and the nature of Cambridge Analytica’s promises to its clients, which likely included US presidential campaigns and possibly even the Leave.EU campaign. We would definitely be a less democratic place without this sort of journalism and yet if I don’t make that online donation to The Guardian once I’ve read up on this story (courtesy of an army of excellent journalists working there) will this sort of investigative journalism even be resourced inside a respected and trusted national newspaper in 10 or 15 years’ time?

Attention Deficit

Dame Cairncross also investigated the changing news consumption habits as readership migrated online. Readers appeared to be getting access to a narrower range of stories as they consumed more online. Put simply, we began reading news for less time and in less depth.

Online behaviour meant news readership became at best perfunctory – characterised by passive scrolling and dipping in and out of eye-catching stories. Remember 2008 to 2018 was the period that saw internet time on smartphones more than double. Average adult mobile-based browsing time rose to 15 hours per week. The smartphone did not arrive until 2007 and mobile browsing accelerated rapidly after the arrival of the Apple iPhone 4 in June 2010.

Post-smartphone, we now spend 40% less time reading news with 42% of all online news consumers skim headlines but rarely click through to original sources. And our consumption behaviour has also impacted how much we value and trust we place in the news we read.

Fake News effect

While online news media consumers paid less attention to what they read, they simultaneously lost some faith in what they were reading as the fake news phenomenon was born. A quarter of readers which consume most of their news online already don’t know how to verify the sources of news they access online. The public has least faith in content coming in via consumer-facing social channels – 24% of people trust what they read there, by comparison to 64% trusting what they read in traditional newspapers.

The Fake News effect sets up a vicious circle in which people have an increasing lack of belief in what they are reading and this in turn feeds into reduced public interest news supply as readers see less value in it.

Attempts have been made on both Facebook and Twitter to verify the sources of stories, flagging this with a blue tick on Twitter for example. But the battle for credibility in online news continues to hot up, no doubt assisted by Donald Trump who is well known for his fake news rants.

Replacing disappearing traditional revenue streams

2007 to 2017 saw revenues from advertising and sales of printed newspapers drop by 50%. Local newspapers saw a 70% drop in revenue over the same period – falling from £4.6bn in 2007 to £1.4bn in 2017. Revenue from sales of papers fell 22% from £2.2bn to £1.7bn over the same 10 year period.

However frantic efforts to replace falling revenues with digital streams of income largely foundered. Only about £0.5bn in online advertising, paywall and voluntary contribution revenues came in.

The tabloids found no success with paywall models and instead chose to drive up the value of their online advertising by battling for increased online traffic using ‘click bait’ fodder and sensational headlines to secure the ‘eye-balls’ for would-be advertisers.

The broadsheets chose either paywall or voluntary online donation models to try to try to replace falling circulation revenue, again with limited success: the Review learnt that only 7% of UK adults are prepared to pay for news online, less than half of the percentage of readers in the Nordics for example.

Yet online advertising revenue was rising fairly fast during the same period so that by 2017 it hit £10.6bn and rose from 16% to 48% of total advertising spending. But traditional news publishers were able to command less than 5% of this windfall, while 54% of it went to the top two online platforms – Facebook and Google of course.

If you look at the aggregate fall of advertising spending with the press over the decade – it fell by a huge 65% from £7.5bn in 2007 to £2.7bn just 10 years later. The nationals effectively went from having a monopoly on advertising together with TV and radio, to losing virtually all their pulling power to a new digital-only monopoly and holding less than a quarter of online advertising spend between them

Online platforms took the whip hand in access to volumes of readers

The online platforms very quickly took control of what news most of us consumed online. The nature of online news aggregators also meant that many readers no longer recognised (or even acknowledged) the original source of the news they were consuming, largely free online.

Publishers were forced to go cap in hand to the online platforms (mainly Facebook and Google) now acting as primary online distributors of their news content. But because of the increasingly unbalanced power relationship between the two parties, distribution agreements with publishers have proved less than generous.

Power shift to the platforms fed lack of advertising value/pricing transparency

Cairncross also shone a spotlight on the lack of transparency around the real value and cost of online advertising as essentially Google and Facebook now control the market and therefore the price that they are prepared to pay for news content which their readers engage with for free. This is one of the areas which the CMA is investigating to see if greater competition and pricing transparency can be achieved.

Bear in mind that by 2018 Google and Facebook together provided regular access to news for over 80% of all UK adults each month. Whilst 10.9m of us use the Apple News app on our iPhones (22% of all UK adults).

Meanwhile, algorithm-based valuation of online advertising is coming under increasing scrutiny for being too opaque. The AdTech being used to provide these valuations doubles or even triples advertising pricing based on likelihood of influencing viewers to buy. This is where Facebook’s highly data-rich preference-based user information comes into its own.

Publishers will need to get much closer to their readers to compete with Facebook. But the likes of the Daily Telegraph is a long way from offering the sort of personalised delivery of advertising which Facebook has been fine-tuning for years.

Battle for direct attention through differentiation

It became increasingly clear that, without differentiating your readers from those of your nearest rival publication online, it would be difficult to protect online advertising pricing and therefore revenues. Size of readership was no longer enough to protect ad revenues.

Titles able to increase direct traffic, were in a better position to preserve ad revenue. While those dependent on social postings, which stimulate browsers to click through to the source of the story, became more vulnerable.

So, for example: The Metro gets 25% of all its traffic direct, HuffPost secures over 20%, while The Sun.co.uk and the i (Independent) gets only 15% each.

The Review also discovered that lower socio-economic groups are less likely to go direct and are more likely to stumble across news via their mobile newsfeed. This of course has made these groups more vulnerable to Facebook-based political campaigning for example.

It is notable how many corrections have been going on as advertising value projections have shifted. Verizon Oath Media downgraded the value of its entire media group by a whopping 94% from $4.8bn down to $200m. Oath Media owns HuffPost, TechCrunch, AOL and Yahoo amongst others.

Number of paid national and local journalists fell by 26%

It was a period which saw publishing groups shedding staff, closing local offices and attempting to reduce pensions and other operational debts. By the end of that 10-year period, the UK was employing 6,000 fewer journalists (declining from 23,000 to 17,000 in 10 years). The industry was retrenching so fast that getting the senior management head space or carving out funds to innovate their way through in the digital age became increasingly difficult.

Part 1 Summary

In summary (crunching the first 55 pages of the Cairncross Review) we have six key points to take away from the digital switch in our news consumption over the last 15 years or so:

- We’re spending less time reading news and thus reading to less depth.

- It’s becoming harder to tell the difference between verifiable and fake news for readers.

- The online platforms are admitting they are failing to stem the spread of fake news. There is a fundamental problem here in that these platforms’ goal is to keep as many users as possible on their platform for as long as possible. They have no remit for protecting the quality and nature of the news content users gain access to from their platforms.

- Quality of news coverage is gradually slipping – a recent YouGov poll found that 47% of UK adults now believe the quality of journalism has fallen in the last 10 years.

- Public Interest News is particularly under attack and this prompts concerns about the creeping democratic deficit from local all the way up to national media level.

- Ultimately, this renders people less able or interested in participating in the democratic process.

In Part 2 we will look at how publishers are beginning the fight back, hopefully supported by judicious Government intervention, innovation and industry wide collaboration. One such is the so-called ‘Ozone Project’ which should offer publishers a way of dicing, slicing and micro targeting its combined 41m readers and subscribers.

Author: Miles Clayton

Published: 11 February 2020

Recent Comments